Today, you can find hydrogenated butter with canola oil right next to trans fat-free margarine. Partially-hydrogenated soybean oil a few aisles down from Omega-3 fatty acids. Your friends tell you that you can eat fat as long as you avoid sugar, while doctors tell you to avoid some fats because they’ll clog your arteries and cause heart disease. Yes, the world of fats is as complex as it is diverse.

But soon, the danger of eating the wrong fat will shrink just a little bit as one of the worst players is going away for good: Say goodbye to trans fat. By 2021, it’ll be gone from store shelves. But before we talk about that, though, we have to look at how this simple nutrient comes about and infiltrates our grocery products.

We’ll start with the basics: Both the fat in your ice cream and the oil in your frying pan belong to a group of nutrients called lipids. Like all other natural chemicals in nature, lipids are made mostly of carbon and hydrogen atoms. And the tiniest of differences in how these carbon and hydrogen atoms arrange themselves affects the consistency, look, and healthiness of your foods.

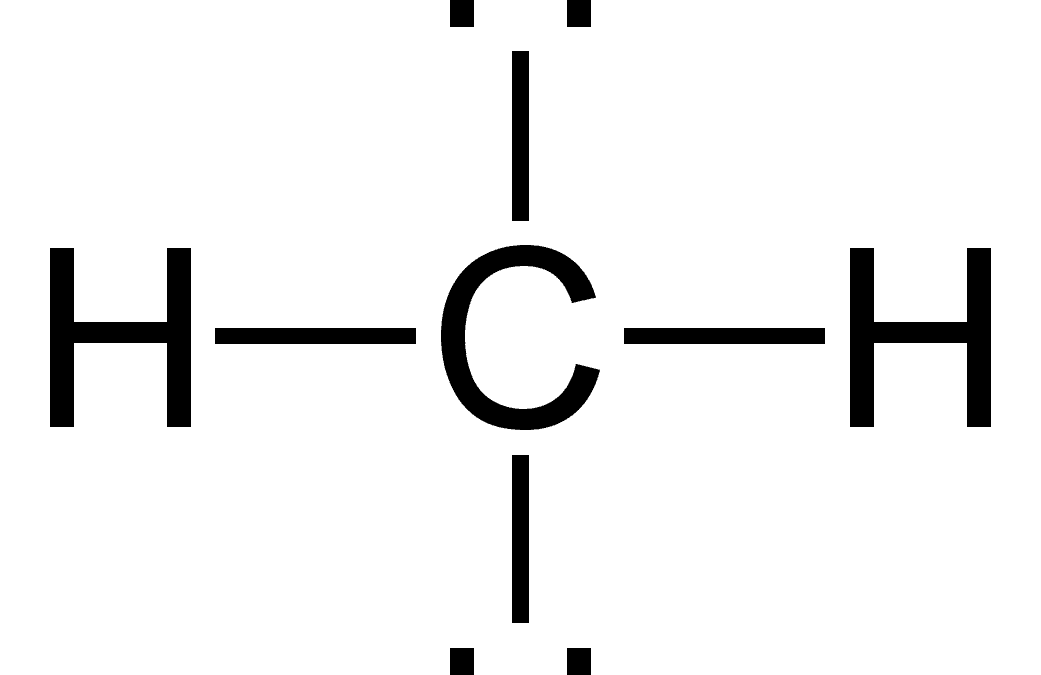

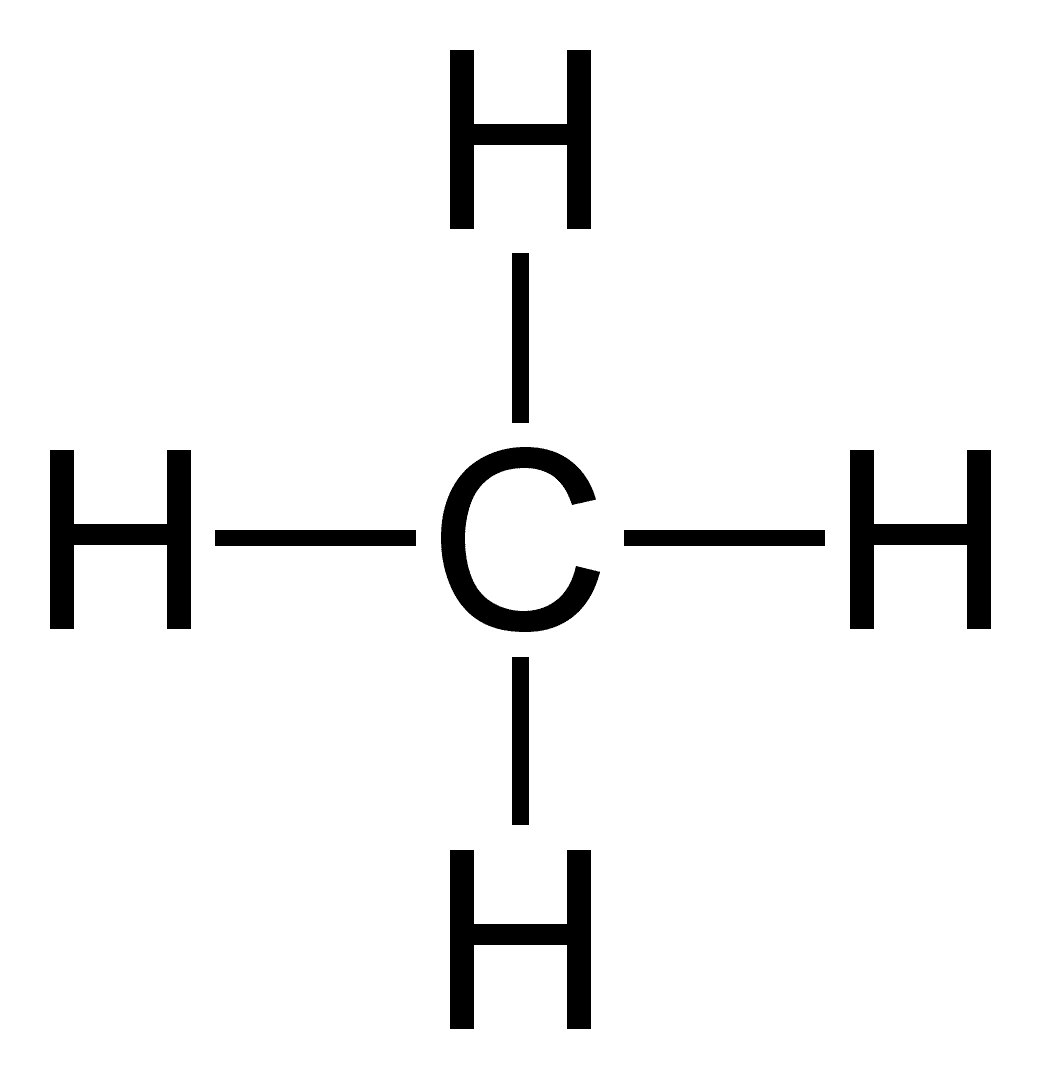

Carbon is a very outgoing element: it likes to make connections, or form bonds, with other elements like hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen. Whereas hydrogen is monogamous and just needs one partner to find balance in its life, carbon needs four other partners to reach the same feeling of satisfaction.

If carbon finds four other hydrogens to partner with, it becomes methane, the primary chemical in natural gas. This is the most basic hydrocarbon (a molecule composed entirely of carbon and hydrogen).

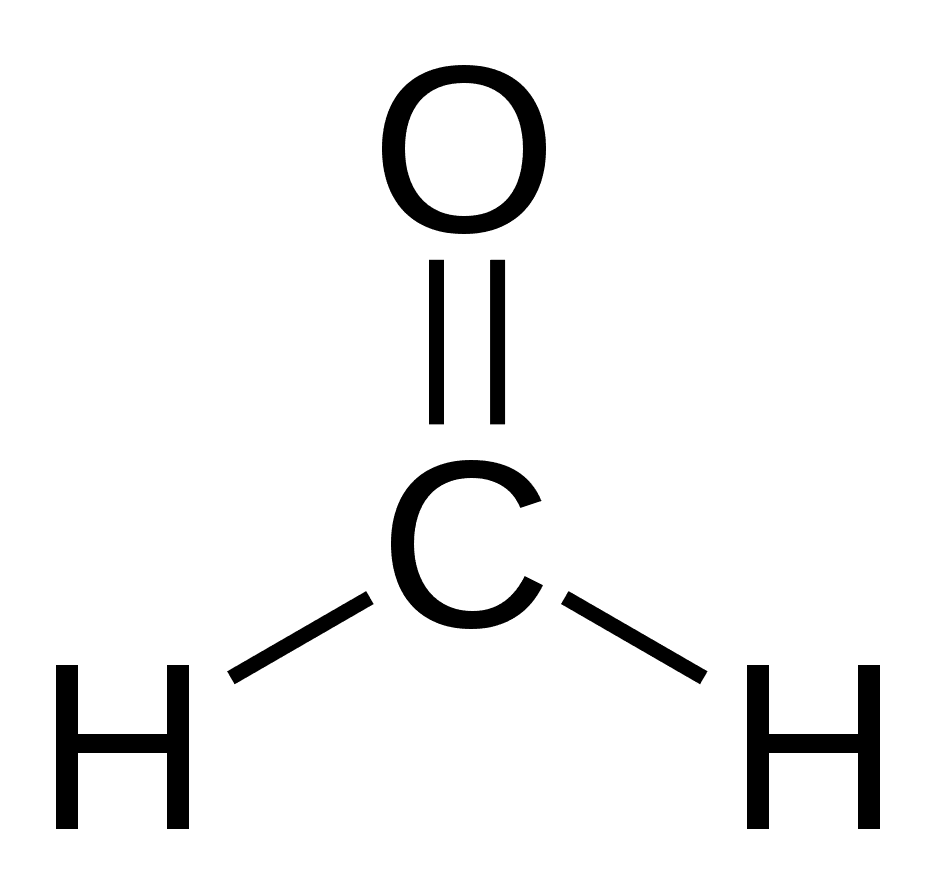

If oxygen comes around, it’ll kick out two of the hydrogens and “hug,” or form a double bond, with the carbon. This makes formaldehyde, which is used to preserve tissues and organs in laboratories.

Once another oxygen comes around, kicks out the last two hydrogens, and hugs the carbon from the other side, you get carbon dioxide.

Finally, remove the two oxygens and add in a carbon. The two carbon atoms will form a triple bond with each other, and hydrogen will fill in the empty slot on either side. This makes acetylene, a fuel that’s used for welding.

Carbon is also the base of your diamonds, the graphite in your pencils, and the sugar, protein, DNA, and of course, the lipids, in your body and in your food. It’s this versatility that makes carbon the building block of life.

Of all the ways carbon can arrange itself, lipids make sense, if you think about it. Take a pool of water (let’s say, the ocean) and throw some carbon atoms in it. They’re going to feel very uncomfortable. Water is polarized, like a battery or a magnet, meaning it has a “plus” end and a “minus” end, and it likes to associate with other polarized molecules. Carbon isn’t polarized, so it doesn’t get along with water. So, in a pool of water, carbon will only want to sidle up to itself. Add some heat and enzymes, and the carbon atoms will join together in a long chain and hydrogen atoms will fill in the extra space.

All of the sudden, you have a lipid.

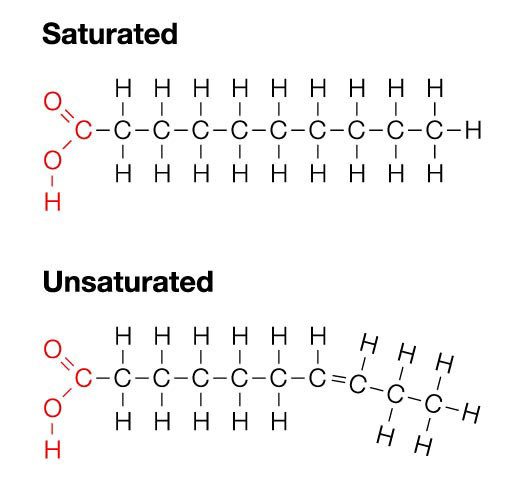

If all of the carbon atoms are bonded to each other through the bare-minimum single bond, it becomes a saturated fat. It’s called so because the chain is as full of hydrogen atoms as it can get.

But if two of the carbon atoms decide to form a double bond with each other, they need to kick out two hydrogen atoms to make room for each side of the bond. This forms an unsaturated fat. Put more than one double bond in your lipid, and you get polyunsaturated fats (Poly = “many” in Greek). Most unsaturated fats are found in the “cis” configuration in nature, which means the hydrogen atoms that kicked out came from the same side of the molecule. This forms a kink in the chain.

Where does this leave us in dairy aisle?

Food manufacturers play around with the hydrogen atoms in fats to make different foods.

When food manufacturers make oils, like canola oil and olive oil, they use unsaturated fats that have the occasional “kink.” These bent chains can’t line up very easily — it’s like trying to line up cooked pasta; it just doesn’t work — so they don’t crowd together as well. This results in liquid oil.

To make butter, they take unsaturated fats and add the missing hydrogen atoms back. This turns them into straight lines that can cluster right up against each, just like uncooked pasta. This makes the fat solid.

But rather than saturating the fat and turning it into a solid block, food manufacturers often partially hydrogenate it so it’s still easy to cut, and so it can melt in the microwave. They sometimes add in canola oil, an unsaturated fat, to make the butter even easier to spread.

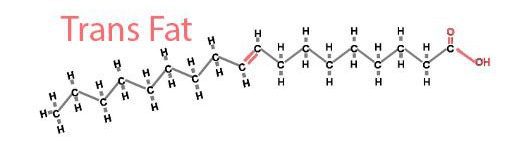

While partially hydrogenating fats makes butter easier to work with, it can also cause problems. Remember, food manufactures start with unsaturated lipids called cis fats. In these fats, the missing hydrogen atoms come from the same side of the molecule, forming a kink. But sometimes, during the process of making saturated fats, the cis fats don’t pick up any hydrogen atoms. Instead, the hydrogen atoms that are already there just switch sides, so the empty slots end up on opposite sites of the lipid. In this arrangement, the lipid can shape itself in a straight line like a saturated fat. Since the missing hydrogen atoms come from opposite sides of the lipid, these fats are called “trans” fats.

Trans fats can be found in nature, but they often sneak up in unhealthy amounts in processed foods. When you see “partially hydrogenated” on a food package, this means the food might have a higher-than-normal level of trans fats because of the hydrogenation process.

Since trans fats line up so closely, they can form solid plaques in your arteries that restrict your blood flow and cause heart disease. But fortunately, trans fats are on their way out.

In fact, the end of trans fats has been a long time in the works. In 2003, the World Health Organization (WHO) decided that trans fat should not account for more than 1% of a person’s diet. Three years later, New York City banned trans fats in fried foods. In 2015, the FDA removed partially hydrogenated oils from their list of foods that are Generally Regarded as Safe, and in 2018, the WHO put additional pressure on the industry by releasing a 6-step plan to remove trans fats from the global food supply.

The FDA’s decision that trans fats no longer safe means that food manufacturers had to stop putting them into their foods by June 2019. But since it takes some time to transition their manufacturing processes, they have until January 1st, 2021 to make sure it’s completely gone.

So, say “good riddance” to trans fats, and eat a vegetable. Your heart will thank you for it.

-

Ben Marcus is a public relations specialist at CG Life and a co-editor-in-chief of Science Unsealed. He received his Ph.D. in neuroscience from the University of Chicago.

View all posts