Deep inside Belize’s Actun Tunichil Muknal (ATM) cave, I discovered a pallid seedling on the bank of a subterranean river. It had failed to develop past its embryonic stage, naked except for its cotyledons, the precursors to its real leaves. Perhaps a passenger on an unwitting tourist’s foot, it had found itself in an inhospitable new habitat. ATM is heavily regulated, allowing only 125 visitors per day, and boasting no permanent light fixtures. Without light, this unlucky seedling was doomed to a premature demise.

In unaltered cave environments, there is no niche for photosynthetic organisms (like the unfortunate seedling) that rely on light from the sun for energy. A cave does not meet the conditions they need to survive, and they do not play a role in sustaining other organisms in the cave ecosystem. In heavily touristed caves (so called “show caves”), however, light introduced by human presence can carve out a niche for photosynthesizers, allowing them to flourish. This phenomenon has a charmingly literal Germanic name: lampenflora.

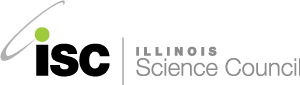

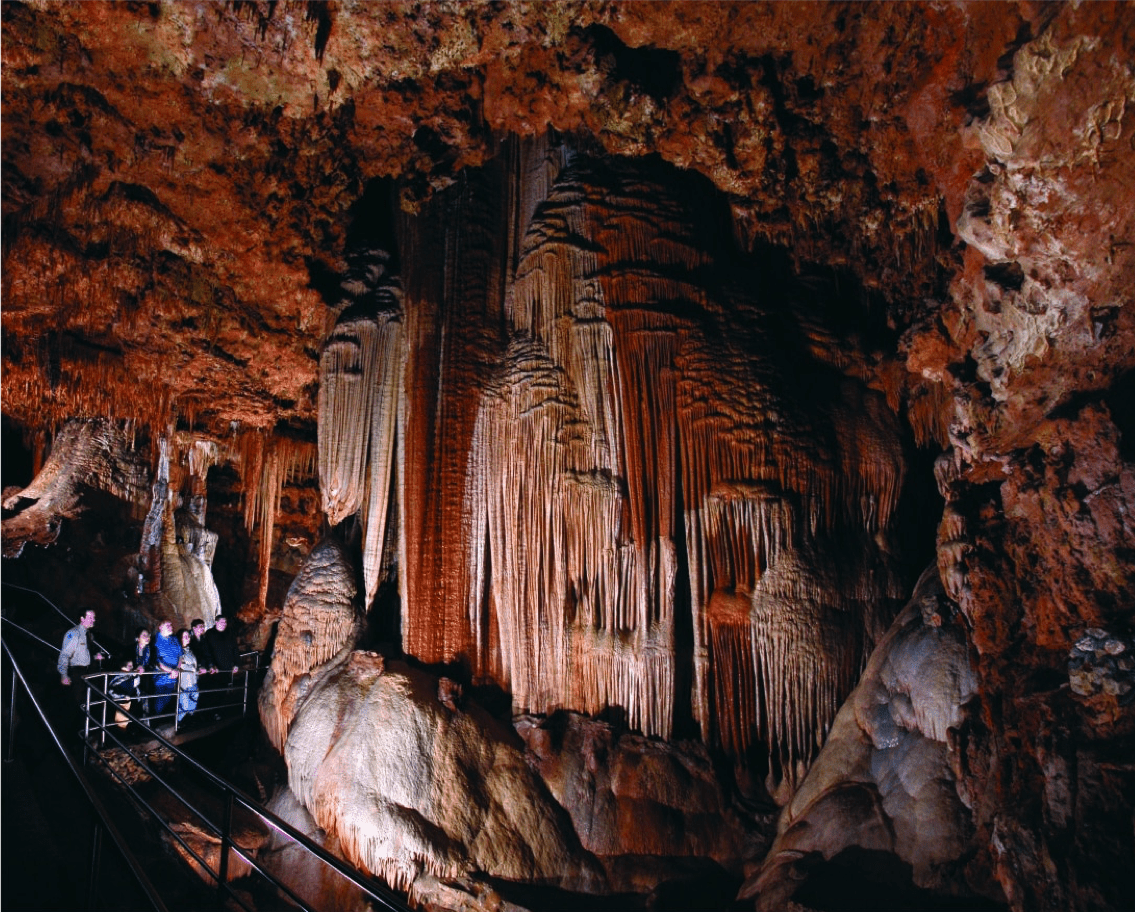

A seed introduced into a show cave with permanent lighting, such as Meramec Cave outside Saint Louis, will have a far different fate than the doomed seedling in ATM cave. Visitors to Meramec will quickly notice that the walls of the cave near the installed lights are lush with an explosion of lampenflora. Plant life is thickest close to the light fixtures, where moss and even small ferns grow. Farther away, the photosynthetic life fades to a faint green sheen of green algae and cyanobacteria on the cave wall, called a biofilm. These single cellular organisms are called “pioneer species” because their colonization of this environment paves the way for other organisms, such as the mosses and ferns, to settle. Thus, the bullseye formation of the lampenflora happens because the areas closest to the light were colonized first, and so reached their mature form (called a “climax community”) first, whereas areas farther away are still in the early stages of development.

While human presence in caves might be good news for photosynthetic organisms, it can shift the balance of the ecosystem, disrupting the native species. Research directly studying the effects of lampenflora on cave ecosystems is limited, but one study conducted in Indonesia uncovered shifts in communities of arthropods (a category including insects and spiders) in caves with lampenflora. The researchers sorted arthropods into two groups based on their role within the cave’s ecosystem: decomposers and predators. Decomposers are typically more common in cave environments because they can consume a broad range of waste as food sources. However, the researchers discovered an increased proportion of predatory arthropods in heavily touristed caves with lampenflora.

The researchers propose that this change in community composition could contribute to destabilizing the cave ecosystem, disrupting native organisms in the cave and beyond. Some species, called trogloxenes and troglophiles, share their time between the cave and the outside environment. Through interactions with both of their habitats, these species can enable changes inside the cave to ripple into the outside world. Therefore, the establishment of lampenflora could have far-reaching effects on the surrounding environment.

While the researchers attribute these population shifts to lampenflora, they don’t control for other factors, such as temperature and humidity, that may be affected by human presence in these caves. While it is clear that humans can disrupt native cave communities, more work is clearly needed to untangle which variables are responsible for these changes.

In addition to lampenflora’s potential role in shifting ecosystem balance, the green oases surrounding light fixtures can present a challenge for the conservation of both natural and anthropogenic cave artifacts. As part of their metabolic processes, the organisms that comprise lampenflora interact chemically with the walls of the cave, causing pH fluctuations that are destructive for cave formations and art. In fact, much of the literature discussing lampenflora focuses on its management and reduction.

Lampenflora are a fascinating, and in many cases beautiful, phenomenon. The process by which they colonize new environments is a powerful testament to life’s resilience. They are also a particularly poignant visual reminder of our power to drastically transform ecosystems throughout the biosphere. Though the changes wrought by human presence in caves are especially obvious and visually striking, they certainly do not stand alone. Lampenflora serve as a symbol of our human ability to create profound ecosystemic change through our mere presence.

-

Roo Weed is a PhD student studying microbiology in the Biophysical Sciences program at the University of Chicago. She earned her BA in Physics from Middlebury College in 2019.

View all posts